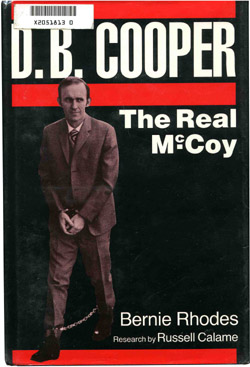

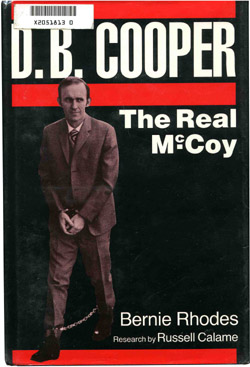

-- D.B. Cooper: The Real McCoy

Compare these sketches of skyjacker "D.B. Cooper", drawn from eyewitness accounts, with photographs of Richard McCoy.

|

| Overnight, Cooper became a folk hero... D. B. Cooper was in a class apart. A ballad of how he had outfoxed the feds hit the airwaves, fan clubs sprang up, T-shirts bearing Cooper's name were sold as souvenirs, and pubs and restaurants opened with neon signs bearing the name of this new Robin Hood. -- D.B. Cooper: The Real McCoy |

Compare these sketches of skyjacker "D.B. Cooper", drawn from eyewitness accounts, with photographs of Richard McCoy. |

Richard McCoy was a devout Latter-day Saint who became a national folk hero when he took over an airplane, collected a half million dollars in ransom for it, and then jumped out of the airplane midflight and eluded federal authorities. Songs, stories, and myriad theories soon emerged about "D.B. Cooper," the pseudonym McCoy used when perpetrating this unlikely crime.

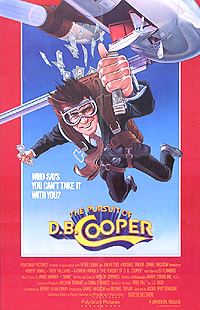

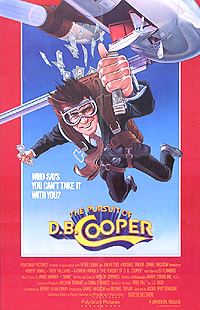

The 1981 movie "The Pursuit of D.B. Cooper" stars Treat Williams (now the star of the critically acclaimed, Emmy-nominated Utah-filmed TV series "Everwood") as D.B. Cooper. Robert Duvall stars as the federal agent pursuing Cooper. The movie does not correctly identify Richard McCoy as the man who used the "Cooper" alias. It posits a fictional character named "J.R. Meade" (Williams' character) as Cooper, and mixes actual facts of the caper with many fictional elements.

Below are excerpts from a well-researched book about Richard McCoy, the actual "D.B. Cooper":

Pages 3-6

Introduction

On 24 November 1971, a lone male Caucasian, using the name of Dan (misidentified by the press as D. B.) Cooper, hijacked Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 between Portland and Seattle and parachuted from the rear stairs that cold, rainy Thanksgiving Eve with $200,000 of the airline's money. Cooper was never found. None of the ten thousand twenty-dollar bills extorted from the airline was ever found in circulation, although many years later $5,880 in damaged bills was dug up -- literally excavated from a sandbar -- along the Columbia River. The Cooper case still remains on the FBI books as the only unsolved airplane hijacking in American history.

Five months after the Cooper hijacking, Richard Floyd McCoy, Jr., a Mormon Sunday-school teacher and Vietnam vet from Provo, Utah, using the name James Johnson, hijacked United Airlines Flight 855 and also parachuted in the dark of night from its rear stairs with half a million dollars. McCoy was caught and convicted in federal court 29 June 1972 in Salt Lake City, Utah. After serving only two years of a forty-five-year sentence, he escaped from one of the U.S. government's maximum-security prisons. After several months as a fugitive, McCoy was killed in a shootout with th e FBI in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

During the course of my investigations back in 1972, I became convinced that Cooper and McCoy were the same man. This, then, is the story of the life of the man who had the ingenuity and courage to execute both of these hijackings. This is also the story of the difficulties and confusion that envelop law enforcement when someone concocts a completely new type of crime -- in this case, holding an airline at ransom, then jumping with the money at night from the back stairs of a commercial airliner in flight. Cooper was the first ever to do this, and, while initially caught off guard, law enforcement quickly adapted to counter this criminal innovation.

My name is Rhodes. I was the chief United States probation and parole officer for the District of Utah in 1972 when McCoy came to trial. My job as chief investigator for the federal courts was different from the FBI's. I wasn't so much interested in the crime itself as I was in the criminal and what provoked him to commit the crime. By the time a criminal case was referred to my office, the crime had been solved, an arrest had been made, and either a plea of guilty had been entered or a jury verdict had been rendered. Then it was my turn to look the offender over, determine why he did it, how he went about it, who got hurt, and, if given the chance, whether he would do it again.

By 1972, I had pulled a hitch in Korea, started a family, graduated with a B.S. in criminology from the University of Houston, and worked as a federal probation and parole officer for a little over ten years. Eleven years later, with twenty-eight years of marriage on the rocks, I'd had enough. I retired. After a couple of years in Pacific Beach, California, getting the cobwebs out of my head, I was invited by friends to use their summer home on Skopelos, an island on the Aegean side of mainland Greece. That was in 1985, the year this book was started. After a little less than a year in Europe, I returned to Salt Lake City. It was at a Christmas party in 1985 that I ran into Russell P. Calame, former special agent in charge of the Salt Lake City FBI office. That was a stroke of luck, because without him, the story would have died the following year. Calame agreed to do the research. He's done much more than that. In many ways, the story is more his than mine.

I knew Richard McCoy, In 1972, following his conviction, I interviewed him and most of his immediate family. However, I never felt comfortable sharing the contents of those interviews with the public. By 1986,1 had decided it might not be ethical or in keeping with the integrity of the federal court to use interviews conducted while I was an officer of that court. I had also concluded it would be impossible to cell the story without the interviews. But what I'd overlooked in Russ Calame was that, although he had been retired from the Federal Bureau of Investigation since 1972, he could still pull rabbits out of his hat.

Not by accident, Calame found out that in 1972 the McCoy family had planned to publish a book and contracted with an attorney in Provo, Utah, Thomas S. Taylor, to act as their agent. The project eventually fell apart, but Taylor had kept the transcripts -- almost two hundred pages of typed, yellow legal-sized sheets that had been gathering dust in his basement for almost fifteen years. Taylor graciously gave his entire file to us in late 1986. It was thirty hours or more of rambling, colorful interviews with Richard McCoy, his wife, Karen, his mother. Myrtle, his brother, Russell, and Karen's sister, Denise Burns.

From these transcripts, I have reconstructed, in the participants' own words, their roles in Richard McCoy's short and troubled life without feeling that I have broken a trust or misused my office. Because the information in those transcripts duplicates most of the information in my own shorter interviews, I have written the interviews as though I conducted all of them to give more immediacy to the dialogue. I have also omitted the usual apparatus of ellipses when necessary in putting the circumlocutions and repetitions of conversation into more readable form.

In 1986, I filed a lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act, asking the federal court to require William Webster, director of the FBI, and Edwin Meese, the attorney general of the United States, to release connecting material from the Richard McCoy and D. B. Cooper files. Some things, after almost twenty years, had been destroyed by routine purgings of the file at the legal, ten-year mark. Other items had unaccountably been lost. Our search for these materials is part of this story. Among the many documents in our files are transcripts of FBI interviews; correspondence with the Department of Justice and with the FBI agencies in Utah, Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, and Virginia; reports of FBI laboratory results; copies of telegrams and teletypes among FBI offices; Air National Guard duty rosters; and searches of newspaper files in six states. Transcripts of the trial, appeals, and private correspondence with agents who worked both cases are pan of the documentation that buttresses our reconstruction. Nor is that all. Calame and I, over the past five years, have also conducted over 180 hours of taped or transcribed interviews with agents, friends of McCoy, and others directly involved in both cases.

I have not tried to diagnose or psychoanalyze Richard or Karen McCoy. Neither is this a rehash of tired old D. B. Cooper theories.

More than twenty never-before-released links in the modus operandi of the two cases are startlingly identical. Most convincing, however, is the disclosure of two personal items that Cooper inadvertently left on the plane before he jumped, objects that members of McCoy's family later independently identified as Richard's.

All names, dates, and events arc factual and are written as they happened back in 1972, with one exception. Out of respect for his family, the name "Maurice Slocum," a pseudonym, is used to protect the identity of one of the FBI agents mentioned in this story. Otherwise, this story is true. It begins in a small town in Utah on Friday morning, 7 April 1972, a few days after Easter.

Pages 7-8:

The Hijacking Begins

7 April 1972, before Dawn, Povo, Utah

Long before the sun had found its way through the frozen peaks of the Wasatch Mountains to the east of Prove, Richard McCoy had stored his luggage in the old gray Plymouth Fury parked at the curb and was backing the Volkswagen out of the driveway. Karen, quickly zipping four-year-old Chanti's snowsuit., picked up little Richard and hurried both children into the Plymouth.

Karen later explained the plan: "Take separate cars south to Spanish Fork. Leave the Volkswagen there and drive together to the Salt Lake International Airport. Then later that night when Richard and the money were safely on the ground I would pick him up, drive him to the Volkswagen, and lead interference for him in the Plymouth in case there were roadblocks. Richard had talked and planned tor months how to hijack an airplane," she added^ "but I didn't really think he would do it. It never dawned on me when we left the house that morning that within thirty-two hours it would be under around-the-clock FBI surveillance."

The McCoy house, as they drove away that Friday morning, looked exactly like its neighbors behind the line of bare-limbed horse chestnut and sycamore trees that arched over the street: they were all small, square, two-bedroom bungalows built in the early or maybe rhe late forties, with matching concrete front porches and slate-colored, over-sized, pitched roofs; they were all made of dark red brick held together with oozy gray mortar. Overgrown pyracantha bushes lining either side of the houses had licked most of the metal-gray paint from the worn wooden windowsills. On the south side of each of the houses, two narrow strips of concrete, separated by unmowed bluegrass and dead weed stems, led to single-car, frame garages in the back.

Prove, Utah, is the home of Mormon-church-owned Brigham Young University, where the number of children per family is twice the national average, the divorce rate is half, and one out of every sixteen people in town either teach, take classes, or do odd jobs for BYU. Provo is a predominantly white, Mormon community, where, except for a few athletes or international students, a person can grow up, marry, have children, and pass on without ever getting to know a black person, a Catholic, or a Jew. Provoans are law-abiding; they normally do not hijack airplanes.

Interstate 15 north links Provo to Salt Lake City. Toward the south, the direction Richard and Karen were driving, it follows a winding, fertile valley with 11,877-foot Mount Nebo visible on the left, perched just above apple and cherry orchards. To the right, Utah Lake goes on for miles, furnishing irrigation water to the small townships -- many with names from the Bible -- of Goshen, Salem, Mona, Nephi, and Spanish Fork.

"At Spanish Fork," Karen reconstructed, "Richard parked the Volkswagen in Central Bank's parking lot at about six-forty-five A.M. and rode with me north to the Salt Lake City airport." They argued most of the fifty miles over the divorce proceedings Karen was threatening to file -- who would get custody of the two kids, how much of Karen's hard-earned money had been spent on airline tickets, guns, and disguises.

"You're a dreamer, Richard!" Karen screamed from the driver's seat of the Plymouth that morning. "You don't intend to go through with this thing! You're crazy. And you're just throwing my money away!"

At the Salt Lake International Airport, Richard dragged his two pieces of luggage from the trunk, kissed the kids through the open rear window, and promised Karen he would call her from Denver at exactly two o'clock if everything was going as planned. "Toodle-oo, Richard, toodle-oo," Karen mumbled angrily, lifting her pale blue eyes to the rearview mirror and flipping the old Fury into drive.

Richard arrived at Denver's Stapleton International Airport at 12:30 that afternoon. It was Friday, 7 April 1972...

Pages 16-18:

Vietnam as a Green Beret, Richard piloted the army's C-13 combat helicopter over hostile territory on more than twenty-five missions. On 12 August 1967, while participating in a search and rescue operation in the jungles near Ap-binh-Hoa, a light observation helicopter lost power in heavy ground fog and was forced to set down. A second American crew flying an armed OH-23G helicopter was sent in to make the rescue from the air as there wasn't room to land. Richard was piloting a third 'copter, giving backup protection. He could see the battalion sergeant major standing on the bubble of the downed chopper waving his arms as the rescue helicopter descended. Suddenly it too lost power and fell to earth, catching the sergeant major in the rotor blades. Both helicopters burst into names.

It was getting dark, but there was enough light from the flames of both aircraft that Richard could see more than a hundred Viet Cong troops snaking through heavy elephant grass some three hundred yards away. "It had to be done, and it had to be done quick," the commanding officer's report read. Richard forced a landing place next to the downed 'copters, his rotor blades cutting through tree limbs as he made his descent. On the ground, he found only two survivors, both hysterical. There wasn't time to sort through the dead. The three of them scrambled for Richard's C-13 workhorse. Richard could feel his helicopter buck as the rotor blades cut through heavy foliage on their way our. The sky was dark, a somber background for the explosions of enemy ground fire and fuel tanks erupting. On 26 November 1967 he received the Army Commendation Medal for Heroism.

Then, on 29 April 1968 he received the Distinguished Flying Cross for yet another rescue. The citation read:

WARRANT OFFICER MCCOY distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions during the early morning hours of 8 November 1967, while serving as a Helicopter Pilot with the Air Cavalry Troop, llth Armored Cavalry Regiment, in the air over a Vietnamese Popular Forces compound at Xa Duy Can, 7 miles northwest of Tanh Linh, Vietnam. Upon hearing that the compound was in the process of being overrun by a large Viet Cong Force, Warrant Officer McCoy volunteered to fly his aircraft to the scene in support of the friendly forces, in spite of poor visibility due to thick ground fog and intermittent cloud layers, and a complete lack of tactical maps for the area. Flying by instrumentation and radio alone. Warrant Officer McCoy located the compound and came under automatic weapons and small arms fire. With the position of the compound marked by a flare and the firefight marked by tracer rounds. Warrant Officer McCoy began a series of firing passes., launching rockets directly into the Viet Cong positions until all his ammunition was expended. Due to his courageous flight and highly accurate fire, the enemy was completely routed, leaving 20 bodies behind. Warrant Officer McCoy's outstanding flying ability and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army."It took me awhile," Karen continued, "to figure out that Richard had to have the excitement. He didn't want to kill anybody, I don't think, and he didn't want to die. He just, pure and simple, wanted to hear those big guns go off". He said he used to lay awake at night, wait to hear the bell ring. He would just take off on a dead run. Be the first one out there in line to go. He just had to have that excitement. As if he was trying to dare death to come."

When Richard returned in 1968 from this second tour of duty in Vietnam, he still wanted to go back. "Our marriage has never been what you would call rosy," Karen hesitated, "but . . . well, I don't know, I guess you could say we were getting along fairly well until he wanted to go back and I couldn't understand this. Why he had to go back to Vietnam."

Karen described her husband as "one of the most honorable, honest, and religious men I've ever known in my entire life." In Vietnam, he baptized one of his buddies under fire. He would fly out on Sundays with his helicopter, collect the Mormon boys, and hold services.

"Richard," Karen said, with possibly the first tears she'd shed in years, "is what I call -- and I've never said this to his face -- my hero." She managed the next words between deep sobs, "An American hero."

Richard was a certified American hero, no question about that. Karen liked that about him. She also liked his looks. His nose was set Just off center, and his scarred high cheekbones gave him the look of a middleweight. He was handsome, in a rugged, uneven way. He had deep-set blue eyes., and his arms were long and muscled. There was always something exciting about Richard McCoy.

Karen, at twenty-seven, had both brains and backbone to go with her good looks and had learned resourcefulness early. She grew up in Canton, Ohio, and was only eight when her father died. Her mother, given to severe bouts of depression and alcohol abuse, became an added responsibility. Karen grew up running the house and caring for her younger sister, Denise. As a high-school junior, Karen suffered from severe headaches and depression that eventually led to psychiatric treatment. She became a Mormon in her teens along with Denise and their older brother, graduated at the top of her class, and was awarded a partial academic scholarship to Brigham Young University.

Richard first came to Provo in 1962 and enrolled at Brigham Young University as a freshman. Then he dropped out for a two-year tour of duty as a Green Beret in Vietnam. Wounded in 1964, he was awarded the Purple Heart and spent the next year at home in North Carolina recuperating. In 1965 he returned to Provo, reentered BYU, and met Karen Burns. They were married that summer. In August 1967, he reenlisted on condition that he go back to Vietnam, and, after a year of intensive training, he did. "It was the excitement, I guess," Richard told me. "The risks you take in combat, knowing death is always one step away."

Pages 22-23:

I had trouble understanding that day how a law enforcer in his latter forties could still possess such trust and optimism. How strange it seemed to meet someone in the "Me Generation" of the sixties who not only made speeches about, bur lived by, a set of principles, consecrated through nearly fifty years of FBI excellence. But I also had a new awareness, after meeting Calame, that Salt Lake City was Hoover's way of showing Calame his appreciation for twenty-some years of calmly chasing top-ten fugitives, armed bank robbers, and confidence men.

Calame's reward -- Utah. It's a strange state. Its image -- or part of it -- for over a century has been of bearded white men in tall black hats tinkering around with an old and often-envied social phenomenon known as polygamy. I've heard that a major airline back in the 1960s used to advise passengers, while taxiing into the Salt Lake terminal, that they were now in Utah and to set their watches back a hundred years.

While the politically conservative and traditional Mormons represent only 55 percent of the population in the Salt Lake Valley, they occupy 95 percent of the seats in the state legislature and 100 percent of Utah's congressional seats. The other 45 percent of greater Salt Lake's nearly 800,000 inhabitants are a mixture of Catholics, Lutherans, Unitarians, and [disaffected] Mormons. Less than one-half of 1 percent of Utah's population is black. Between Mormons and non-Mormons, social, political, and religious issues of varying weight and importance become a part of daily life in newspaper editorials, TV talk shows, and demonstrations at the Capitol Building.

First-time visitors to Salt Lake City are generally not disappointed when they get a look at its wedding-cake architecture around Temple Square and the long line at Snelgrove's, where icecream worshippers gather. Brigham Young, who led the Mormons to Utah in 1847, gets the credit, at least in folklore, of personally laying out the city. From the uncompromising block of Temple Square, he laid off streets running in the four cardinal directions, each one wide enough to let two yoke of oxen pulling a covered wagon turn around without backing. The streets are still as wide and dean as they were thenm, but skyscrapers, malls, and glass office buildings loom above them.

Page 35:

At about 8:12 P.M., along Interstate 5, somewhere in the vicinity of LaCenter, Washington, north of Portland, Cooper walked out the rear door, sat for some moments on the rear stairs, and suddenly disappeared with the $200,000.

But Cooper left behind two telltale pieces of physical evidence which the FBI, for the next twenty years, would keep a secret from the press, from the public, and from a long list of D. B. Cooper impostors who over the years would be interviewed one by one and eliminated. In preparation for his jump, Cooper removed his narrow, dark clip-on necktie and milky mother-of-pearl tie clasp and left them on seat 18E. FBI agents searching the Cooper plane in Reno found them. Six months later in Utah, the tie and tie clasp took on new importance in the Richard McCoy investigation.

Overnight, Cooper became a folk hero. His hijacking had required intelligence, daring, specialized skills, and above-average strength. The FBI was familiar with some of these characteristics in America's criminals who specialize in confrontational crimes like kidnapping and armed robbery. But D. B. Cooper was in a class apart. A ballad of how he had outfoxed the feds hit the airwaves, fan clubs sprang up, T-shirts bearing Cooper's name were sold as souvenirs, and pubs and restaurants opened with neon signs bearing the name of this new Robin Hood.

Page 38:

"Our wedding day was not," as he put it, "what we had planned it to be." Richard and Karen had planned a quiet family celebration in Louisburg, North Carolina, in an ivy-colored Mormon meetinghouse that August of 1965, but an argument between Karen and Myrtyl "got loud and nasty," according to Richard, "and our wedding plans had to be kept secret."

Page 40:

According to Myrtle, "Karen and Richard had a wedding we'll never forget. That little Mormon church there in Raleigh was just packed with people. As soon as the bishop pronounced them man and wife, Karen and Richard walked out of the church and down the stairs, arm in arm. All of Richard's friends had the car decorated with old pots and pans and old shoes and toilet paper and every ribbon they could find in all of North Carolina."

Pages 91-95:

The Arrest

Sunday, 9 April 1972, Provo

"They're harder to see at night," remembered Karen McCoy. "Harder to see than ordinary people. With the lights off in the living room that Saturday night, we could see cars moving back and forth Jnd then they would park at both ends of the block. But we couldn't see anyone in them. Richard must have known it was just a matter of time, because he went to bed about midnight without saying a word. I couldn't sleep. I just hv there trembling next to him. Thinking tomorrow would be Sunday, Sunday someone might not live to tell about. Wondering what would happen to the kids. And thinking how close we had actually come. I must have drifted off around four thirty, because at five the next morning -- barn! barn! barn! They practically tore the door down getting in. I can remember Richard upping over Denise as he jumped out of bed and went running barefoot for the living room. I could hear loud voices corning from the next room, and then I heard the soft clicking sound of handcuffs.

When I finally came to my senses, I wrapped a robe around me, grabbed the baby, and ran out into the living room. That's when I saw Richard sitting on the couch with his hands cuffed behind his back and his head down between his legs. Four or five FBI agents were standing over him with their guns drawn. The big cheese, Special Agent in Charge Calame, wearing the gray Stetson har, was looking down at Richard reading him his rights.

"Looking back now, I should have made them break the door down. Stuff was strung all over the place. The gun and grenade were in one place, the typewriter and notes were in the kids' room, and then the half-million dollars. Well, where do you hide a half-million dollars in a house this small?"

The FBI agents drove Richard to Calame's office in Salt Lake City, where he was charged by complaint with violating Section 1472(i), Tide 49, U.S. Code, Aircraft Piracy, and Section 1472(j), Title 49, U.S. Code, Interference with Flight Attendant. (Later, the federal grand jury indicted him on one count of aircraft piracy.) He was rushed before U.S. magistrate A, M. Ferro, where he was advised of the charge, the penalty, and his right to counsel, then ordered to be held in jail without bond. At a little after eight o'clock, they let him call Karen. He was fine, he told her, asked about the kids, Karen remembered, "and then said, 'be sure and take care of everything.' He said, 'Ev'ry-thing,' Mr. Rhodes, like that, so I knew he meant for me to hide ev'ry-thing."

Salt Lake City's Deseret News started off that Sunday morning with a UPI story about a cataclysmic earthquake in southern Iran, which, according to a witness, had hit like the end of the world on Judgment Day. Judgment Day in Tehran was mild compared to Judgment Day in Provo, Utah.

Sunday mornings in Provo for the past 125 years meant, for Mormons, attending a full day of church services in which they are urged to follow the dictates of their faith and to turn from sin. Now, someone in Provo had actually sinned, had been caught at it, and was being carted away to be punished. Inside 360 South 200 East, Karen was hissing frantically at Denise, "Denise Burns, you have got to get up, get yourself dressed, take these two kids of mine to the babysitter's, and help me hide all this stuff." Outside, the neighborhood had taken on a toy-balloon atmosphere. Youngsters, perched high on their fathers' shoulders, pointed at the house from across the street. Photographers, television crews, and a front yard full ofcuri" ous onlookers had to be held back by some FBI agents while the rest sat waiting for the green light from Calame, shovel in hand and anxious to start digging cavernous holes in the MeCoy yard.

When Denise and Karen got back from dropping the children off at the babysitter's, they had already had one screaming match in the

driveway and Karen had threatened to turn Denise in to the FBI. Denise had caved in.

Back in the house, Denise's first action was to start wiping away at her typewriter keys.

"Denise," snapped Karen viciously, "what do you think you're doing with that typewriter?"

"Cleaning my prints off it," responded the frightened Denise.

"Stupid!" Karen snarled. "It's your typewriter. Whose prints would they expect to find on it?"

Denise hadn't thought about that.

"I wasn't very nice about it, Mr. Rhodes," Karen admitted, flipping her head back. "But I had to scare Denise into helping."

"And the house was still surrounded, was it?" I asked.

She nodded. "They didn't have their search warrant yet. And they knew they weren't getting in my little old house without a valid search warrant."

"What time are we talking about, Karen? Before noon or after?"

"Just about noon, Mr. Rhodes "

"All right, now, go ahead with what you were going to do."

"Well, basically, we took everything out of all the boxes we could find. Clothes, toys, and then we went down to the bottom of this big cardboard box and took the money out. It was all there for them: the grenade, the gun, sunglasscs, gloves. And of course we had to do this very quietly because they were sitting around all over the yard.

"We didn't know how much time we had before they came charging in like the Light Brigade. As it turned out, we had several hours. Jfl had to do it over, I would have cleaned the gun. But then what good would that have done? Burned the gloves. But what for? Sweet little Denise helped me put some of the money in this three-foot-long stovepipe. There was a little crack in the corner of the window where the drapes didn't fit so she would duck every time she went by. When she got her hands on the money, she was so nervous she jerked some of it half in two on the end of the stovepipe."

They covered the end of the pipe with a plastic sack. The sack fell off, spilling money. Richard kept calling, chatting coolly and unconcernedly but hinting clearly to Karen's sensitized ears that the FBI was About ready to search the house.

Karen dug out the two cardboard boxes that their phonograph speakers had come in and shoved the money into them. "We tried to hide them as high as we could in the room adjacent to the kids bedroom, but we knew it was really a waste of time."

Between Richard's calls from Salt Lake, calls started coming from California, North Carolina, and New York. Karen smiled mirthlessly, "Here we are still stuffing the grenade and gun in the money box and telling people on the phone, 'I'm sorry., but we don't know what you're talking about.' " The doorbell was ringing, too. Karen made a call of her own, one to Sister Mathews from their local Mormon ward. (Mormons call each other Sister or Brother.) To the terrorized Denise, that was the final nightmare. "Karen had called Sister Mathews because she felt she was starring to tall to pieces. Karen threatened to kill herself," Denase said, "because her life was over without Richard McCoy and she had driven him to do it, and all she wanted to do now was just die. Sister Mathews said, no, she shouldn't, and of course talked to her in a sensible manner like anybody would. Me, I was too upset to say anything so I left the two of them alone" Karen left with Sister Mathews, ordering Denise to guard the house until she saw the search warrant. It came within minutes after Karen left. Denise abandoned the house to Jim Stewart and scurried over to the neighbor's house where Karen was drifting off, the doctor's tranquilizing shot taking effect. "She just laid there," Denise recalled, "on the couch saying, 'My life is over. My life is over. They've got the wrong person in jail,' she'd say. 'I belong there, not Richard. All over, gone forever.'

"So I thought the FBI had the case all wrapped up. Looked like it to me. They found the money and other incriminating stuff. Then all of a sudden they -- Stewart -- start working their way around me, asking me questions about where he landed, who was with me when Van leperen called, and I said no one, I was alone babysitting the two children, then I say, 'Whoa, I gave it away, so you guys I don't say no more."'

"What time Sunday was this, Denise?" I asked.

"About two-thirty or three in the afternoon."

"Where was Karen when Stewart talked to you about what you were doing that Friday night?"

"Okay, Mr. Rhodes, Karen went to the hospital. A Dr. Robert Crist came and took her to the Utah Valley Hospital. She was held in Room 374, under another name, Karen Adams. Because she was still threatening to kill herself."

The lead story in the Deseret News that Monday morning read:

RANSOM FOUND-MINUS $30

PROVOAN IN JAIL ON AIR PIRACY CHARGE

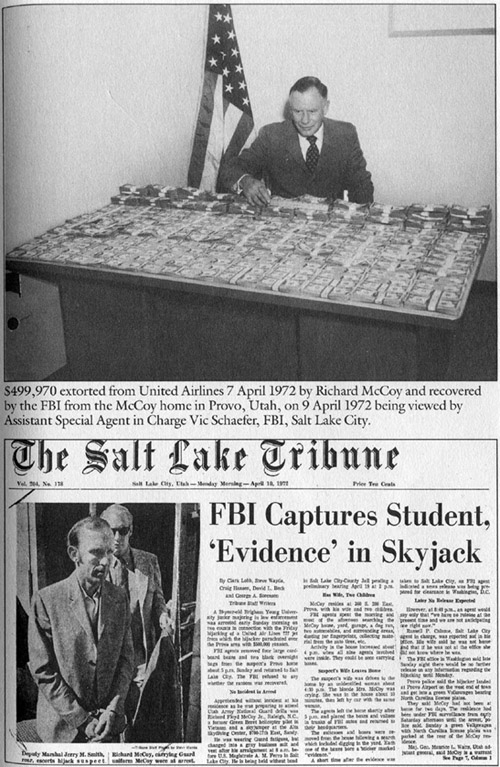

FBI agents have recovered $499,970 of the $500,000 ransom paid to a skyjacker who parachuted from A United Airlines 727 jetliner over the Provo area kite Friday.

The money was in a cardboard box and was among several items seized Sunday by agents armed with search warrants who combed the apartment [sic]y yard and two automobiles belonging to Richard Floyd McCoy, Jr., 29, 360 S. 200 East, Prove.

McCoy is being held in the Salt Lake County Jail without bail on federal charges of air piracy and interfering with a flight attendant.

He was arrested about 5:30 A.M. Sunday as he was leaving his home to attend a Utah National Guard drill. He offered no resistance to FBI agents.

The FBI had been Watching the house since Saturday afternoon on the quiet, tree-lined residential street about two blocks ii'om downtown Provo.

The stake-out of the house apparently was based on information first supplied by McCoy's sister-in-law and a good friend of McCoy who is a Utah Highway Patrolman.

The same edition also carried a press release from Special Agent in Charge Russ Calame:

An inventory of evidence seized at the home of Richard Floyd McCoy, Jr., 29, Provo, charged in a $500,000 skyjacking of a United Airlines plane was provided today by the FBI. The list included: a blue and white parachute, black parachute harness and a military type flight suit ... a green military canvas bag, a black crash helmet, a brown coat, a silver colored man's wrist watch and . . . two electric typewriters. A cardboard box containing various items of clothing, a pistol, a holster and a black glove was confiscated.

Almost as an afterthought came the final item: "Also found was $499,970 in U.S. currency, most of it still wrapped in bank bands."1

1 The missing $30 was never located, but could probably be accounted for in the bill Richard used to purchase a drink at the Springville Hi-Spot and the money he gave Karen and Denise for supper Saturday night. Other money in the house was not inventoried.

Page 97-102:

The Judge: Willis W. Ritter

Because aircraft piracy was a federal crime, Richard McCoy would be tried in the United States Court for the District of Utah, presided over by Chief U.S. District Judge Willis W. Ritter.

Judge Ritter inspired a lot of different feelings in people, most of which, I think, were variations of terror. Even I, who was probably as close to him as anybody on this side of the grave -- or the other, for all I knew -- and really liked the old judge, never made the mistake of forgetting that Ritter was a landmine and that the slightest tickle could set him off. I'm not sure why Ritter liked me. It wasn't so much that I was Catholic, like him, as it was that I wasn't Mormon. More, I suspect, because I wasn't a Republican. I was from Harry Truman's home state of Missouri, and, as Ritter used to tell people, "That's grounds enough to trust a man, even if you can't believe anything he tells you."

In 1962, not long after I'd finished college and left Houston, I was standing before Judge Ritter's bench, along with the defense attorney, the prosecutor, and the defendant, a young man in his late twenties up on a charge of dealing heroin. It was my job as probation officer to make a brief background report prior to sentencing. One of my pious points was his prior experimentation with lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD, the hallucinogen of choice for the "Me Generation." Reeking outraged morality, I heard myself say, "By the early age of seventeen, Your Honor, this man was already experimenting with LDS."

Ritter looked up. "Experimenting with what, Mr. Rhodes?"

Behind me, I could hear belly laughs being swallowed by men facing as much as forty years in prison. LDS is the acronym tor Latter-day Saint, a shortened form of the official name of the Mormon church: the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

"Your Honor," I said, "I misspoke myself." I waded gamely into that sentence again and I'll be damned if it didn't come out "LDS" again! By now those muffled belly laughs had turned into what resembled grand mal seizures.

"Your Honor," I began for the third time.

"No, no, Mr. Rhodes," Ritter said, "that's enough for one day. It isn't really that important whether this young man was experimenting with LDS or LSD. Just the slightest exposure to either one and a man begins to hallucinate."

I wouldn't say that my faux pas started any great and glorious friendship, but Ritter did have a sense of humor, and I got along with him as well as anybody else.

During the weeks following Richard's arrest, he received visits and phone calls from lawyers as far away as New York volunteering to represent him pro bono (without charge). But for one reason or another, he rejected all offers and asked Judge Ritter for courtappointed counsel, paid for by the federal government under the Criminal Justice Act.

Ritter didn't mind that and emphasized to his court clerk, John Brennen, "I want a lawyer in this McCoy case, John, that has knee action and fluid drive. With the death penalty at stake, this case is going to end up before the Supreme Court, and I can't afford to have this thing botched up. There's been an incessant drumfire of scurrilous and malicious plotting back there to run me ofFthis bench. So I want a good lawyer appointed in this case. The best trial lawyer we've got around here." Brennen appointed David K. Winder.

Winder was a Stanford Law School graduate, just under six foot three, athletic, in his late thirties. Born into a wealthy Mormon family, he leavened his dress and manner with apologies to the poor and less fortunate. Winder had caught Rirrer's eye as an assistant United States attorney during the mid-sixties prosecuting criminal cases, but had since joined the prestigious law firm of Strong and Hanni as a full partner.

Dave and Pam Winderwere vacationing with their three children in San Diego when the clerk of court reached him by telephone.

VVhen Ritter's voice burst on the telephone line, it came like a cloudburst on a tennis match. Summer clothes were suddenly stuffed into suitcases, reservations for leisurely dinners overlooking Mission Bay were canceled immediately, and the family Mercedes headed northeast again.

On 26 May 1972 Assistant United States Attorney Jim Housley stood and advised the court that Richard McCoy was present for arraignment. Judge Ritter had the clerk read the charge. Dave Winder then reminded the court that prosecution witness Dr. Eugene Bliss, director of psychiatric services at the University of Utah, had examined McCoy and that the court should hear him on the question of competency before a plea could be entered.

Dr. Bliss, a short, wiry man whose thick, black hair was always in his eyes, took the witness stand that day. He was succinct and easy to understand. Ritter liked that. Dr. Bliss found Richard to have above-average intelligence -- the capacity to formulate intent and understand the charges -- and to be capable of assisting in his own defense. Dr. Bliss stepped down. Winder then told the court that there was also a motion pending to have a Dr. David Hubbard from Dallas, Texas, an expert on the mental makeup of hijackers, and Dr. Peter McDonald, a renowned psychiatrist from Denver, examine Richard.

"Why?" Ritter demanded, then read Winder a brief chastisement for being frivolous with the taxpayer's money, and ruled against him, derouring to laud Dr. Bliss. "The reputation of the University of Utah School of Medicine," Rirrer said, "the Psychiatry Department, and its director, Dr. Bliss, extends far beyond the state of Utah. Dr. Bliss has told us that Richard McCoy has the mental horsepower to formulate intent, knew what he was doing, knows what he's charged with now, and can assist you, Mr. Winder, in his own defense. That's what this court is interested in, not whether he was picked too soon or wound too tight. Take his plea," Ritter said.

Richard entered a plea of not guilty, and his trial date was set for 26 June 1972.

Willis Ritter turned seventy-five that year. He stood five foot seven and weighed in at 240 pounds. He described himself as a Democrat, a Catholic, and a civil-rights advocate who had been graduated from the University of Chicago Law School in 1924 and from Harvard in 1940 with a doctorate of jurisprudence. A law professor at the University of Utah for nearly twenty-five years, he had a reputation for teaching more in the first two hours of class than others taught all year. Ritter had been appointed to the federal bench as Utah's chief judge in 1949 by President Harry S Truman over the protests of conservative Mormon leaders. From his earliest days, Ritter had never been shy about stepping over or on top of cultural lines in Utah, and age had only made him more splendidly cantankerous.

"Harry Truman," he would intone after a judicious pull on his whisky glass in chambers, "was one of the greatest statesmen the Western world has ever known. His philosophies, his decisivenes^ under fire, even his appointments, will go on to influence the entire world for the next five hundred years." Pausing just long enough to freshen his glass from a quart of twelve-year-old Wild Turkey bourbon, Ritter would continue, "Truman took office during some of this country's -- the world's -- most turbulent times. Truman had to decide alone whether or not to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that brought the Japanese to the bargaining table. What a terrible decision for a man to have to make! He was responsible for the Berlin Airlift and George Marshall's European Recovery program after the war ended.

"And, by God," he would chortle, "not the least of Harry Truman's more controversial legacies was the appointment of yours truly to the federal bench. Those sniveling little Mormon sons-a-bitches wore a path between here and Washington, D.C., trying to hold up my appointment. Now they come parading into my courtroom as if nothing ever happened. Well, I know exactly who they are! I got myself a copy of the FBI investigation where they went into my background -- who they talked to and who said what. And I got a copy of the Senate Judiciary Committee's hearing! And I remember word for word what was said."

Spittoons had long since been removed from Ritter's seventy-five-year-old courtroom, but an imaginative eye could still trace a circle of errant tobacco shots on Ritter's worn lime-green carpet where they had once sat. The two west windows behind the bench were framed by light-ash wooden pediments. A huge gold American eagle was set in creamy marble on the west wall between the windows. This would be where Ritter would hold the McCoy trial -- but not always where court was held. The majesty and paralyzing power of the court was in His Honor's presence. A few years earlier, Ritter, in a clearing beside the San Juan River in southern Utah, had tried a suit between the Department of Interior and the Navajo Nation over a herd of wild mustangs. The saying went back then, if you were an Indian, a black, or just plain poor and happened to be right, you wanted Ritter to hear your case. If you were wealthy and wrong, you didn't. "Over the past thirty years," his bailiff Spence Van Noy used to say, "this old courtroom has heard more picas, confessions, and prayers for forgiveness than the Cathedral of the Madeleine four blocks up the street, where even Ritter occasionally stops to remind himself he's only a federal judge."

Ritter, although married, had lived alone for the past twenty years at the old Newhouse Hotel, located on the southwest corner of Main Street and Fourth South directly across from the federal courthouse. Built in the early 1900s, its marquee bragged about the liquor lounge, advertised dancing, and was the antithesis of the Mormon-owned Hotel Utah located next to the Mormon Temple four blocks up Main Street. The Newhouse was where the Democrats had held their fund-raisers and political victory parties over the years, but now its dangerously decaying red brick exterior was a detailed reflection of Utah's Democratic political climate. The interior was also old, rococo but comfortable.

From Suite 1000, located in the far northeast corner of the tenth floor, Ritter could look down and across and keep an eye on those who worked for him in the federal court. "You gotta watch 'cm like a hawk," he'd say, "watch 'cm constantly, or nothing ever gets done." The afternoon sun had, over the years, cracked and peeled a lifetime of white paint from worn wooden windowsills, leaving them yellow and the windows hard to open. His combination bedroom, living room, and kitchen had the loud overhead scars to remind the parade of senators and governors who dropped in to pay their respects that it had once been two separate rooms. Furnished with antique Louis XIV chairs, couches from the Mediterranean, an Early American four-poster bed, and paintings and drapes purchased from the Franklin Delano Roosevelt estate, it was an eclectic old gathering i; place where people and ideas went to become legends.

I remember seeing Ritter's reflection once in the long mirror that stood in the entrance hall. The evidence of trauma, suddenly apparent in the reversed features, was startling: many small strokes had accumulated over the years to give the face in the mirror a twisted, ^cstalt configuration. Independent facial characteristics, pulling against each other, as if in pain, would as always, just in time to take the bench, again become coconspirators in reconstructing the image of Utah's seventy-five-year-old chief federal judge. It's reasonable to speculate that Charles Darwin could have singled Rittcr out personally to prove his theory of natural selection. Given the same environment for the next hundred and fifty years, two additional arms may have unfolded . . . making it possible for His Honor to thumb his nose at the United States Supreme Court, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, the GEEEEESUS-KURRRIIIIST of Latter-day Saints, and the Republicans -- all at the same time.

I can also remember standing in mortal awe of Willis Ritter, convinced that, after a few strong bourbons, I would make an absolute fool of myself by blurting out something that didn't make a bit of sense. King Solomon, compared to Judge Ritter, I thought, ran nothing more than an ordinary court of domestic relations back then. Yet, somehow there was something strangely familiar in the way both men handled small courtroom disputes.

Page 103:

The First Two Days of the Trial

Monday-Tuesday, 26-27 June 1972

The line of witnesses, spectators, and reporters began on Main Street and gradually worked its way down to the federal courthouse, up two flights of stairs, through electronic metal detectors manned by U.S. marshals, and into Bitter's courtroom.

By the time Bitter's gavel came down for the first time, Bichard had been the subject of a long article with photographs in Time and the hook for an expose in the Wall Street Journal on how hijacking affects the airline industry. I heard a rumor that Myrtle and Karen had already sold book and movie rights to Der Stern, a West German publishing company.

Helped from the back seat of the government's old Plymouth that warm Monday morning by U.S. marshals, shackled hand and foot to six feet of belly chain, Richard looked straight into the barrel of NEC'S live On-The-Spot television camera. Out-of-town newspeople had made hay with Brigham Young's Utah and Richard McCoy's Mormon connections. There were now, the press said, three kinds of Mormons -- practicing Mormons, jack Mormons (nonpracticing), and skyjack Mormons.

Ritter had a policy against chains and handcuffs, so the marshals stopped just outside the door and took them off. I was standing against the wall next to the north door when Richard and the marshal entered, then looked around, confused, I thought, about where LO go. Richard stood dignified and erect, scanning the courtroom. His eyes found his mother about the time mine did.

Myrtle was seated on the front row...

Page 164:

From where I sat that morning, the face across from me seemed identical to the composite drawing of D. B. Cooper that lay between us. Except for the color of the eyes, of course. Richard's eyes were light blue, close together. Something about his nose and scarred cheekbones gave him the look of a lanky prizefighter. Richard's eyes rested often on the Cooper drawing. He was clearly curious, but he never touched it with his hands. To me that seemed unnatural.

"If you can," I began softly with what Calame and Theisen felt to be their second strongest piece of evidence, "and I know this was a while back, Richard, but try to remember where you were last Thanksgiving. November 25th," I said, "and the day before Wednesday, November 24th, 1971."

His complexion turned the color of potted ham and his head turned toward the drawing of Cooper -- but his small blue eyes stayed on me.

"Thanksgiving? Well, let's see, Mr. Rhodes. Thanksgiving is still a holiday, isn't it, so naturally I would have been around the house. 1 didn't have school and I didn't have guard, so" -- he's onto me, I thought, and then he said -- "I was home. Why?"

"Careful now," I tell him, "about how you answer these next few questions. Any one of them could cause you a whole lot of trouble."

My next few questions would come very slowly, in deliberate whispers. This was a questioning technique I used to control the rhythm, the opposite of a rapid-fire, staccato approach used generally by two or more interrogators capable of keeping track of the answers. Mine was a simple litany of short questions that shifted the suspect's attention to hearing what was said -- followed back and forth by a series of nervous rejoinders.

"Cook or clean," I asked, "or help Karen with anything she might remember, Richard?"

"Yes," his voice was low like mine; he cleared his throat. "1 cooked, yes, and helped Karen with Thanksgiving dinner."

"What time of day was this you helped Karen and Denise around the house?"

"Most of the day I'd say, Mr. Rhodes. I'm sure I was home until after six o'clock."

"What rime did you eat?" I asked.

"Two o'clock?" he answered, with a rising inflection, as though he were asking a question, "two or two-thirty?"

Page 171-173:

Second Interview with a Hijacker

Sunday 2 July 1972

Richard was housed in maximum security on the third floor with half a dozen guys in for murder and other serious crimes against the person, separated from the general population. The social structure in a prison is pretty much the same as it is on the outside. A prisoner gains status according to his accomplishments. A bank robber commands more respect than a liquor-store bandit, a burglar more than a bad-check writer, and so on. The number of arrests a man has isn't important. Some small-time convicts have criminal records as long as the Dead Sea Scrolls and can't find out when they're supposed to be in court. A federal prisoner however, suggests class and commands the respect of guards and inmates alike. Richard was not only a daring criminal but also a well-publicized one. He'd made Time magazine and was being treated as a celebrity.

It was a little after nine o'clock that Sunday morning when Mormon services let out in the jail chapel and Richard was led into the interview cell. Without so much as a good morning he dropped a very official-looking 5x7 envelope in front of me and flopped down in one of the two steel-latticed chairs. I opened the envelope and read a letter that managed to make itself perfectly clear:

THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF

LATTER-DAY SAINTS

THE OFFICE OF THE STAKE PRESIDENT

June 8,1972Richard F.McCoy:

This letter is to notify you that on June 6, 1972, the Provo Stake High Councii Court, in accordance with the law of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, excommunicated you from the Church on the grounds of skyjacking and extortion.

Excommunication from the Church means that the rights and privileges of Church membership have been withdrawn, and that you no longer possess the priesthood of God. You may attend sacrament and auxiliary meetings and general conference sessions. Tithing and other contributions may not be paid, but you should be encouraged to deposit such funds until the time of your possible baptism.

It is sincerely hoped that the day will come when through your genuine repentance you may once again be associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Repentance is not only to desist from a sin but also to keep the commandments of the Lord.

Provo Stake Presidency

Roy W. Doxey

Bliss H. Crandall

Dean E. Terry

I looked up at Richard. He was wearing baggy, faded blue jeans, the kind the Navy used to issue, anchored to his lean hips with a piece of black shoestring. A white T-shirt, almost too small for his broad shoulders, labeled him PRISONER SALT LAKE COUNTY JAIL. He'd lost Twenty pounds, he told me. I remember thinking that he'd also lost something else. It was his will to live, I could see, that had taken the beating. Sunday looked to be a long day for both of us. The day before, I had intentionally come into the interview without pencil or pad. I wasn't going to push him too hard the first day. Loosen him up a little, I had thought, plant a few of Theisen's and Calame's D. B. Cooper seeds and see what sprouted Sunday. This morning, I pulled out a pocket-sized dictaphone and set it on the table between us.

Richard and I had no more than given it a couple of good one-two-threes when one of the jailers swung open the heavy steel door and set a cup of coffee in front of me. "Would you like a cup, Richard?" asked this young, easygoing guard wearing a new stiff brown sheriff's uniform, as if to say, since you've been excommunicated. . . .

"I'd better not," Richard answered, as if he wasn't completely sure himself what his status was. "Still against the Word of Wisdom, you know," studying me from his side of the long, green metal table. I lit up a Marlboro to go with my coffee, took a couple of deep drags, and asked him if he still felt himself to be a Mormon.

"Yes," he answered, "I guess I do. And you, Mr. Rhodes," he asked, "what are you?"

"Catholic," I said, at least I guessed I still was, and suddenly the guard was standing next to us again pouring more ninety-octane coffee. It wasn't me he was buttering up. It was Richard, Probation officers are generally looked upon by jail guards as would-be priests who at the swearing-in ceremony got cold feet and now wander around aimlessly under the Father Flanagan Doctrine: there is no such thing as a bad boy.

We talked about Richard's sentence. He sounded desperate but beaten. He could'receive a forty-five-year sentence, and not less than twenty, and there was no reason to hope Judge Ritter would give him anything less than the maximum. As if turning through the pages of his life one at a time, he said, "I can't even comprehend forty-five years. I'm only twenty-nine now, and I feel like an old man. Even if I got out in say thirty years," he said, "Chanti ..." Tears came to his eyes. I looked away. He stopped talking for a minute and then went on. "Chanti would be thirty-five years old; Rich, thirty-two." There was a long pause. I looked at him again. This time, his eyes were steely. "I don't think I'll put them rhrough that," he said, "or me either."

Karen, two days before, on Friday, had confessed: "Richard McCoy is hell-bent, Mr. Rhodes, on taking his life, and he's asked me to bring something to him at the jail to do it with. I haven't made up my mind yet," I can still hear her saying thoughtfully, "but this whole thing, you understand, is as much my fault as it is his."

Richard and I that Sunday morning thumbed through a standard probation worksheet and recorded his family and marital history, military service, financial situation, and health (physical and emotional), then took a statement in his own handwriting of how he went about taking over United Flight 855. Richard added at the bottom, for Ritter's benefit, that he wasn't surprised by the jury's verdict. "They had no other choice, Your Honor," he wrote. Then he gave Judge Ritter and Dave Winder both a bunch of nice adjectives. I believe he meant them.

Pages 177-181:

Ritter on a Monday Morning

Monday, 3 July 1972

Just before noon on Monday, 3 July, a call came into my office on a private line labeled "Judge Ritter" in a discreet but definite red.

"Rhoooowdes," I answered in a long, deep voice.

"Riiiiiitter," Ritter answered back, and we both had a belly laugh.

"Where are you, Judge?" I asked. "Hotel?"

"Hotel," Ritter said, "but I'm on my way over"

"How about a few oysters on the half shell?" I said.

"Blue point?" Ritter asked.

"Fresh, plump blue point," I told him. "At the Hilton."

"No, no," Ritter said, "I've just eaten an orange." Then he laughed again and added, "and two apples. Clothes won't fit me, but I need to see you in chambers. A little before one," he said. "I need to go over a few things with you."

Ritter's necktie, when I got there, was already thrown to one side, his shirtsleeves pushed up rather than rolled. He was writing as if his life depended on it. His desk was about as old as he was. It was made of heavy dark walnut, too big for most judges even back then, when being a federal judge really meant something. A waist-high pedestal on his left held a leatherbound dictionary about the size of an apartment house. On his right stood a brown-shaded world globe the size of a Volkswagen. Pushing himself far enough away from his desk to be comfortable, he said, "It wouldn't surprise me to find out I've spent as much time answering complaints instigated by these sons-a-bitchin' Mormons the past quarter of a century as I have out front trying lawsuits. Put an eye on this thing," Ritter said, handing me a dozen or so yellow handwritten pages addressed to the United States Congress. "Tell me what you think of it."

The Honorable Peter Rodino"Whaddya think?" Ritter asked, after I'd had a chance to read through most of it a couple of times. "It's like you insist everyone else write," I told him, "brief and straight to the point." The line where he called the Deseret News the Deserted News, I rmember thinking, was beneath him but nothing to spend a half day rewriting, so I said it was good. How do you tell a man like Ritter, who had corresponded as friends with Learned Hand, the legendary justice of the Second Circuit, that he ought to rewrite something, let along rethink it?

Chairman, House Judiciary Committee

Dear Congressman:

This morning the Salt Lake Tribune arrived with my breakfast with an article about the House Judiciary Committee meerin" the day before. That meeting and a previous secret meeting of the Sub-Committee concerned me very much.

I have been a United States District Judge for nearly thirty years. Because I am a working Judge I have long recognized the obligation to keep my own counsel and not speak out for publication. I have something of a reputation for refusing to talk to the press. I told N.B.C. this week that: "I am an old hand at telling the press where to go."

However, the so-called "judicial controversy" about me has gone too far so I enter the lists in defense of my own good name. I protest against any more ' "secret" meetings with mv detractors. I want to meet with them face-to-face. I want the opportunity to present my side of the matter -- the truth. Before the prestigious Committee on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives recommends another Judge for Utah, I most respectfully request an opportunity to be heard. This is of the utmost importance to me. This incessant drumfire of malicious and scurrilous character assassination must be laid to rest once and for all. The Tribune article reported that: "During the debate Representative Ramano L. Maxxoli, D., Kentucky, wanted to know if there is also a 'religious overtone' in the Utah judicial controversy. 'That's preposterous -- that's malicious and can't stand the light of day,' replied Representative Sanrini, whose father-in-law is a Mormon L.D.S. Stake Patriarch in Nevada.

"Again Representative Sanrini emphasized he was offering his amendments in behalf of Representative Gunn McKay, D., Utah, and in the interest of dealing with "the judicial nightmare' in the Utah Federal District Court.

"Representative Santini again mentioned the Writ of Mandamus before the U.S. Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver to bar Judge Ritter from hearing any cases involving the Federal Government. Another member of the Committee stated, however that there had been no action taken on the Writ."

Members of the Judiciary Committee, I say to you that Representative Santini is wrong on both scores: One, there is no "judicial nightmare in my Court" and, two, it is damned right, there are religious overtones in this judicial controversy -- and worse. That is what it is all about.

Malicious Mormonism, McCarthy-Nixon "dirty tricks" and conspiracy to bring down a Federal Judge are written all over it by the extreme right elements in the Republican Party.

Two of the Mormon Church's principal character assassins and muck rakers are its TV station, K.S.L., and its daily scandal sheet, the Deseret News known widely as the Deserted News. The Mormon Church has taken over practically every other public office in the State of Utah. They have been trying for a long time to take over the Federal Court for the District of Utah. The extreme Rightist Republicans, the John Birch Society, Nixon "dirty tricks" element has been fighting me for thirty years. They fought my appointment by President Harry S Truman in 1949. In 1950 they fought and defeated Senator Elbert D. Thomas, who recommended me to President Truman for appointment to the Federal Bench.

Having failed in his vicious efforts to defeat me. Mormon Stake President Arthur V. Watkins (a Stake President is an administrator governing several bishops), seeking to fence me in, succeeded in obtaining a second Federal Judgeship in Utah, and appointed a Mormon of his choice to that Judgeship. Not only that, Watkins also succeeded in appointing a man of his choice to a vacancy in the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Judge David T. Lewis. Former Republican Governor J. Bracken Lee had earlier given Lewis a State District Judgeship to fill a vacancy there.

Shortly after the second Federal Judge took office -- very shortly thereafter he petitioned the Tenth Circuit to adopt a rule for the assignment of cases between the two of us. This the Circuit did. As a result of this Order, I, as Chief Judge, have had nothing whatever to do with the assignment of cases in our Court. The Circuit Court Order set up sort of a lottery. One of the falsehoods widely circulated is that as Chief Judge I abuse the power of assignment. I had nothing whatever to do with the enactment or the provisions of the law which said I can hold the office of Chief Judge until I die or retire. Congress enacted the law, and at that time several judges were affected by it. As a matter of tact, I found out about it while sitting in San Francisco in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. U.S. District Court Judge Chase Clark, of Idaho, was also there. The San Francisco Judges were kidding him about it. The important point about this Chief Judge furor is that it is a very small matter except for one thing -- the Constitution of the United States is involved. The Constitution forbids Bills of Attainder Article I, paragraph 9, provides as follows: "No Bill of Attainder . . . shall be passed."

It would be unconstitutional to enact a repealer of the so-called "Grandfather Clause." The "Grandfather Clause," as it is called, will be inoperative if our Court ceases to be a two-judge Court, i.e., becomes a three-judge Court and this is the reason these character assassins want Congress to create a third judgeship for Utah -- they can't wait for me to die, and they don't give a damn that a third Federal Judgeship, where it is not needed, is a very costly matter.

I guess Federal Judges have constitutional rights, [but] after living in Utah most of a lifetime, it makes one wonder. I have confidence that your Committee will let this legislation take its usual and ordinary course through sub-committee, and full-committee., with opportunity for hearings. So many Representatives and Senators have judgeships in the Omnibus Bill it has a lot of pressure for passage.

The pressure for passage of the Omnibus Judgeship Bill does not appertain to whether a repeal of the "Grandfather Clause," or a bill creating a third Federal Judgeship for Utah. Time can and should be taken for hearings on these matters. It has been part of the tactics of the sponsors of these two proposals to rush them to passage.

Most respectfully submitted,

WILLIS W. RITTER, Chief Judge

United States District Judge

District of Utah

"And another thiing," Ritter said, "while you're here. I didn't give you enough time the other day with that McCoy kid. Take as long as you need," Ritter said, in an agreeable, friendly manner, most people, I thought, ought to see. "We need to be extra, extra careful around here for awhile," jiggling his jowls a little like Richard Nixon.

Pages 187-189:

To Prison

Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, July 1972

Richard was returned to the Salt Lake County Jail and, because of his long prison sentence, was assigned to a maximum-security prison in Pennsylvania. Prison designations then were made in Washington, D.C., and teletyped to the marshal's office in Salt Lake City. For security reasons, no one -- not the judge, the prisoner, nor his family -- was told when or where the transfer would be made. Hijacking a marshal's car hadn't happened for awhile, but such stories still circulated in the marshal's service. Organized-crime figures iiiid "high risk" prisoners got special attention. So did Richard.

Two deputy marshals left the Salt Lake County Jail before daylight Thursday, 20 July, heading east, with Richard in the back seat. Six feet of belly chain had been threaded through his belt loops, fastened to handcuffs in the front, and locked to leg irons at his ankles. Highway 80 east through Parley's Canyon was a steady twelve-mile winding climb to a 7,000-foot summit. For the marshals, it would be one of the most dangerous pieces of highway between Salt Lake City and Denver, their next stop. Traffic, as they had planned, was light and their unmarked, brown 1969 Plymouth, rigged with a powerful 450-cubic-inch interceptor engine, seemed half-asleep, even at seventy miles an hour. Richard, with help from the deputy marshal seated on the front passenger side, knelt in the back seat looking through the rear window. He watched as Kennecott Copper Corporation's huge smokestacks blew sleep from the eyes of its morning shift. Sunshine forced its way through thick niountain pines and perched atop the Mormon temple. Karen would already be up, getting ready for work. The kids would still be asleep.

At Parley's Summit was another inconspicuous brown 1969 Plymouth parked facing west. A U.S. deputy marshal leaned against the front fender holding binoculars in one hand and a 30.06 in the other. The marshal driving .Richard's car only nodded as he passed.

In Brighton, Colorado, that evening, Richard was logged into the Adams County Jail as a federal prisoner in transit and housed in the drunk tank. When the marshal arrived the next mornins to check out his prisoner, Richard was gone. Deputy Sheriff Robert Hodge's routine morning duties included transporting drunks, vagrants, and misdemeanors jailed during the night to city court for arraignment. During the night, Richard had switched wristbands with a drunk driver. The next morning when Benjamin Namepee's name was called, Richard answered, "Here,3'' stepped forward, and joined the group bound for Judge Hallick's court to be arraigned. "He told me he was sick," Hodge told the judge, "so I took his handcuffs off and walked him down the hall to the restroom. The minute I turned my back, Judge Hallick, he bolted." Captured late that same afternoon several blocks from the courthouse, Richard was wrestled back before Judge Hallick, still insisting he was Benjamin Namepee.

With no one the wiser, Richard entered a plea of not guilty and asked to be released on his own recognizance. "Deputy Hodge," he told Judge Hallick, "hit me, kicked me in the groin, and called me dirty names."

Judge Hallick accepted his not-guilty plea, looked down from the bench, and said, "Mr. Namepee, I know Deputy Hodge. He's a good man and if he did what you say he did, I can tell you right now you had it coming." Benjamin Namepee was still snoring when Richard was returned to the jail, where the U.S. marshals finally untangled the mystery.

Late Monday evening on 24 July, the day Mormons in Utah were celebrating the arrival of Brigham Young in 1847, that same marshal's car turned off Interstate 80 in north-central Pennsylvania and headed south on U.S. 15. One mile north of the small farm community of Lewisburg stood eight tall gray guard towers. Behind them lay twenty-six acres of concrete, steel, and razor wire and eleven hundred federal prisoners. Built during the Great Depression to hide America's mean and unpredictable, it loomed against the Appalachian foothills as deadly and incongruously as a nuclear power plant. A mausoleum for misfits, local people called it.

When the gates closed behind prisoner number 38478-133, Richard McCoy, he became a resident of Dog Block where, four cells down the long catwalk lived a veteran of penal institutions, Melvin Dale Walker, age thirty-two, male Caucasian, five foot ten and 180 pounds. A thousand miles of bad judgment had brought him to Lewisburg Federal Prison. He would be Richard's partner in his second prison break.

Pages 200-201:

Rule 35 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure allows the sentencing judge 120 days subsequent to any appeals to reduce or modify the original sentence. Ritter often did. Accordingly, Winder asked Ritter to reduce Richard's sentence to the minimum -- twenty years. Myrtle added her pleas. Karen, she said, had been unable to find a position teaching school in the Cove City area because of the publicity, and Myrtle was doing her best "to furnish them a home with her limited means.'" She concluded hopefully, "I know that you have great love in your heart for your fellow man and I beg you do something to help my son." Richard wrote me on 23 January 1974, asking me to appear with Winder in any hearing he could get from Ritter. And he also wrote directly to Ritter, explaining his background. It was an illuminating, even moving recital:

During my formative years, it was still the in thing to serve one's country so at nineteen I followed in my father's footsteps and enlisted in the army. During my seven years of active duty, I strived to get into the best units and volunteered for the toughest and most challenging training. After completing parachute school and volunteering for the Green Berets, then came two more years of training in advanced demolition and guerrilla warfare. In 1964 I was sent to Vietnam as an advisor to the South Vietnamese forces where, during combat operations, I was shot and wounded. I've witnessed the death of many good friends. That experience was so distressing that I left active duty a few months after returning home. In trying to get my head together, I decided to return to college. That was in the spring of '65. There I met my wife Karen and married her the following summer. After that I went to work to support my family, but my personal life was not working out so I returned to the only life that offered a challenge. I reenlisted, and volunteered for helicopter training. After a year of intensive training, I returned to Vietnam in 1967. You are aware of a few of my experiences mentioned by my lawyer. As he said., I was awarded the Commendation Medal for Valor. I only mention that to illustrate that I have never shirked my duty in the face of danger and actually sought out difficult assignments. After Vietnam, I served two years in Germany, but in the spring of 1970, after seven years of active service, I deferred to the wishes of my wife and ended my military career. I was scheduled at that rime to return to Vietnam for a third tour of duty, but my family, being aware of my habit of getting into things, was concerned that I was pushing my luck. Perhaps they were right, but there are worse things than dying honorably in the service of a man's country. Considering what's happened since, along with the disgrace and suffering my family has suffered, an honorable death would have been preferable.

After leaving the army, I moved to Prove and enrolled at Brigham Young University where I majored in law enforcement. Due to my age and limited finances, it was necessary to carry heavy academic loads, enroll in summer sessions, and take night classes. But I also found time to serve in the Utah National Guard, work part time as a salesman, and devote time to the church and the Boy Scouts.

I'll bet those Scouts loved him, I thought irrelevantly when I got to this point. But I wonder how all those good Mormon bishops and good Mormon parents are explaining to their teenagers that they should never under any circumstances think for even one minute that Richard McCoy was a fine, upstanding model for youth. Richard went on to explain his medical condition, the future of an invalid that awaited him, and the constraints of establishing a career to take care of Karen and the children. Then he continued:

Maybe you're wondering whether I was capable of harming anyone. If you don't mind, I will go back for a few moments to give you a better insight into my personality. Some of these incidents you may be aware of through the trial and presentence report.

During my first tour of duty in Vietnam, I was wounded. The only reason. Your Honor, was because I was unable to kill another man up close.

On January 8, 1972, three months prior to my arrest, I assisted in a life-saving mission involving an airplane crash. There were three of us directly involved. We were members of the Utah National Guard and were utilizing a guard helicopter. As the aircraft commander, I was directly responsible for the success or failure of the efforts involved. The downed aircraft crashed in trees and deep snow on the side of Mount Nebo, forty miles south of Provo. The three men on the ground were seriously injured and were suffering from exposure. The crash site was at...

4 CRASH OUT OF LEWISBURG

Lewisburg, PA. (UPI) 8-11-74 -- Four armed convicts, including a former Mormon Sunday School teacher involved in a bizarre 1972 hijacking, crshed a commandeered garbage truck through a gate at a federal penitentiary Saturday and disappeared into the central Pennsylvania mountains.

State police, FBI agents and local authorities searched a heavily wooded area 15 miles west of here for Richard F. McCoy, 31 and three other convicts. McCoy was convicted of hijacking a United Airlines jetliner April 7, 1972, obtaining a $500,000 ransom and then parachuting at night near Provo, Utah.

The three others, all convicted of armed robbery, were identified by police as Joseph Havel, 60, Philadelphia, serving 10 years; Larry L. Bagley, 36, of Iowa, serving 20 years, and Melvin D. Walker, 35, serving a total of 55 years for four bank holdups and one escape.

State police said the convicts had at least one gun and some knives.

"They don't have much to lose," a state police spokesman

said. An FBI spokesman said the terrain was some of the most rugged in the state.

Authorities used two police helicopters, about 30 state troopers, FBI agents, and other Jaw officers in the search.

The FBI said the convicts showed a gun to a prison guard at the first of two back gates to the maximum security prison. The guard opened the gate, the FBI said, and the inmarcs then crashed the truck through a second gate to freedom.

About 15 miles west, in the small community of Forest Hills, the convicts accosted a man and two women and stoic the man's car, the FBI said. The man and two women, who were not identified, were left bound but unharmed.

Pages 218-219:

GRAB 2 LEWISBURG ESCAPEES HUNT 2 OTHERS IN N.C. BANK ROBBERY

NEW BERN, N.C. (AP) -- Authorities say four men who robed a Pollocksville, N.C. bank were convicts who escaped from the federal prison at Lewisburg, Pa., last Saturday.

Officers said three men walked into the bank and took an estimated $10,000 at gunpoint, then fled in a car driven by a fourth man.

They said the bandits then switched to another car with Ohio tags. It was subsequently spotted by a police helicopter on an unpaved logging road in the Great Dover Swamp, about 15 miles west of New Bern.

Officers abord the helicopter exchanged fire with the fugitives as they abandoned the vehicle, police said. Officers said no one was hit in the burst of shots.

Arrested later as some 50 officers swarmed into the area were Joseph W. Havel, 60, Philadelphia and Larry LeRoy Bagley, 36, Des Moines, Iowa.

Still being sought were Richard F. McCoy Jr., 32, of nearby Cove City; and Melvin Dale Walker, 35.

Page 225:

The Killing

9 November 1974

Virginia Beach, Virginia

Karen and Richard reminisce softly that night in the front seat about the children, their little red house in Provo and a lot about the Mormon church. Melvin told Calame and me that Richard was still agitated about being excommunicated. "I heard something, good or bad, about the Mormon church and Joseph Smith, its founder, almost every day," Melvin said, shaking his head, "so I ought to know." Religion had been a big part of their daily conversation.

Page 227:

"Then we drove down to Gatlinburg, Tennessee, and spent the night at a Howard Johnston. We had the money out on the ed counting it when Richard turned on the TV. The movie was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. It was like watching ourselves. We counted out $76,000 -- enough, as Richard liked to say, to indulge ourselves for a while longer."

Page 237:

Epilogue